Fukasaku and Scorsese: Yakuzas and Gangsters

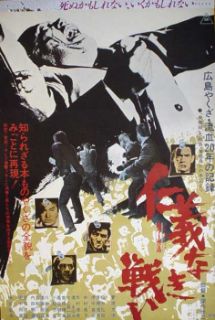

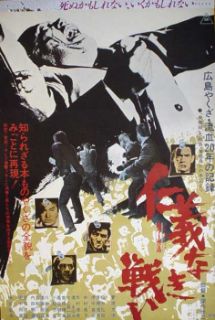

JINGI NAKI TATAKAI JINGI NAKI TATAKAI

(Kinji Fukasaku, 1973)

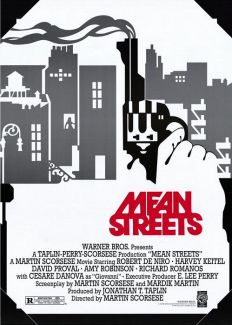

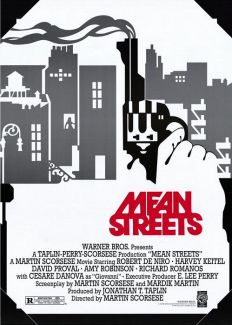

MEAN STREETS MEAN STREETS

(Martin Scorsese, 1973)

|

As Mark Schilling points out, yakuza and Hollywood gangster films have long constituted distinct film genres. Likewise, both genres have evolved over the years (1). Paul Schrader argues that the yakuza film bears little resemblance to its American or European counterparts. He carries on saying that the yakuza film does not reflect the dilemma of social mobility seen in the Thirties gangster film genre, nor does reflect the despair of the post-war film noir since it aims for a higher purpose, a moral purpose that springs from the giri-ninjo (giri, social obligation; ninjo, personal inclination) conflict, an essential theme in yakuza films (2).

From a historical perspective, both the Japanese and Hollywood gangster films have evolved at a different pace and their genre conventions have comprised different themes. A confluence of themes and narrative devices, however, are observed in two gangster films conceived within different national cinemas and socio-historical backgrounds and released in 1973, one Japanese, JINGI NAKI TATAKAI (Battles without Honor and Humanity, directed by Kinji Fukasaku, and the other American, MEAN STREETS, directed by Martin Scorsese. Both films marked a point of departure from the gangster and yakuza film genre conventions up to that point. This essay will examine the similarities and differences between these two films and respective genres, and how themes, initially belonging to one or the other film genre, were discarded and take up by its counterpart. Although, both films were released the same year in their countries, JINGI NAKI TATAKAI some months earlier, there is no evidence that either director was aware of the other's work. Furthermore, MEAN STREETS was not released in Japan until 1 November 1980 (3), so it is quite unlikely that both directors directly influenced each other in any way. And although Scorsese's MEAN STREETS is, to some extend, a homage to gangster films of the thirties such as THE PUBLIC ENEMY or LITTLE CAESAR with the added new realism of the era inserted through innovative film techniques such as hand-held camera, colour saturation, jump-cuts and slow-motion, Fukasaku's JINGI NAKI TATAKAI is a rejection of the idealized depiction of the yakuza in the ninkyo eiga ("chivalry films") of the 1960s.

The American Great Depression and the coming of sound marked the beginning of a new kind of realism in Hollywood films. New genres emerged that challenge the idea of the American dream, with its opportunities for prosperity and success, upward social mobility and social equality for all. The gangster film became, at the beginning of the 1930s, a reflection of society. The gangster became a tragic hero that rise to power through crime as the only alternative to succeed. The Production Code forced producers to shift the emphasis from the gangster as a tragic hero to the gangster as a social victim, emphasizing at the same time that crime does not pay. The figure of the gangster changed radically in the 1940s and 1950s. The heroes in these films were mostly private or police detectives or some other enforcer of the law. Gangsters, even when in prominent roles, were always the adversaries. Not until 1967 with Arthur Penn's BONNIE AND CLYDE, a film set again during the American Depression, were gangsters, once again, represented not just as tragic heroes but also as revolutionary ones. The release of Coppola's THE GODFATHER in 1972 helped even more to mythologize the figure of the gangster, in this case the Italian mafiosi.

|

In Japan, although film critic Keiko McDonald cites earlier examples of yakuza films such as Daisuke Ito's CHUJI TABI NIKKI (Chuji's Travel Diary, 1927) or Hiroshi Inagaki's MABUTA NO HAHA (The Mother He Never Knew, 1931), the heyday of yakuza films really started at the beginning of the 1960s, in the form of the ninkyo eiga (chivalrous film), being its first example Tadashima Tadashi's JINSEI GEKIJO: HISHAKAKU (Theatre of Life: Hishakaku, 1963).

JINSEI GEKIJO: HISHASAKU

JINSEI GEKIJO: HISHASAKU

(Tadashi Sawashima, 1963)

|

This film established a new narrative formula for yakuza films that would be used in one variation or another in over three hundred films before the decade was out. It helped to consolidate a revived star system (4). The periods were generally late Taisho to early Showa (1923-40) and, like the Hollywood gangster film, their settings were primarily urban. Good yakuza are portrayed as living up to the jingi code, and dying by it. Jingi is the moral and ethical code of honour for the yakuza. As McDonald states, "The yakuza experiences his own version of the characteristic Japanese tension between opposing values of giri and ninjo" (5). "Jin expresses the Confucian virtue of benevolence; gi, the values of justice and rectitude...the element of rectitude yields the concept of absolute loyalty to the Organization, its boss (oyabun) especially" (6). The righteousness of the oyabun is underlined by having him always wearing Japanese traditional clothes. |

Gregory Barrett argues that as the yakuza film combines elements of the samurai film, the yakuza code of jingi can be seen as a modern version of the samurai's bushido code, and the yakuza as present-day samurai(7). Unprincipled yakuza are portrayed as only being interested in money. Their dishonourable bevahiour reflects Japan's modernization and Westernization and the consequent corruption of traditional social values of engagement. Honourable and dishonourable yakuza must fight it out in war of moral values.

THE PUBLIC ENEMY

THE PUBLIC ENEMY

(William Wellman, 1931)

|

According to Schrader the enormous success of THE GODFATHER in Japan encouraged Toei film company to infuse its yakuza productions with a more "documentary style". This led to the development of a new genre, the jitsuroku eiga (true story films)(8). This claim seems rather puzzling, if not contradictory, since the style of THE GODFATHER is far from documentary. The beginning of the film, for example, unfolds among contrasting scenes of very dark tones in interior shots, a reflection on the machinations of the Mafia, and the bright exteriors of don Corleone's (Marlon Brando) daughter's wedding. THE GODFATHER shares the narrative of the ninkyo eiga with its emphasis on family loyalty, mafiosi code of honour and criminal world justice. Schrader, quoting Tadao Sato, explains how duty can be more important than humanity in ninkyo eiga (9). This aspect can be also be observed in THE GODFATHER when, for example, acting out of revenge, Michael Corleone (Al Pacino), now the new godfather after his father's death, ignores his sister's pleas and orders the killing of her husband, Carlo, who helped in the murder of their brother Sonny (James Caan). The giri-ninjo conflict pervades Michael Corleone's decisions leading to a cycle of decepction and escalating violence depicted in a highly elaborated montage, far removed from any documentary style. Rather that in THE GODFATHER, jitsuroku eiga finds its Western counterpart in a film like MEAN STREETS.

|

Certainly, films like THE GODFATHER or THE VALACHI PAPERS (Terence Young, 1972) were extremely successful in the Japanese box office. However, Fukasaku claimed he was not consciously aware of having been influenced by any of these two films. Moreover, he did not even find them interesting as, he argued, they failed to portray among the mafiosi ordinary characters holding any feelings of remorse. The films mass appeal in Japan, however, was evident as their titles were featured in newspaper advertisements promoting JINGI NAKI TATAKAI (10). Fukasaku believed his seventies films were seen by society as too brutal and felt rejected by mass audiences (11). Interestingly enough, in succeeding decades, his innovations in both technique and depiction of violence became mainstream. Similarly, if Scorsese's MEAN STREETS brought freshness to the gangster film genre with his realistic and unglamorous view of the personas and lifestyles of small-time gangsters in Little Italy, by GOODFELLAS (1990), in a storyline resembling THE VALACHI PAPERS, he attached gangsters with a mythical quality. MEAN STREETS in many ways shares the giri-ninjo conflict that prevails in the yakuza film. The giri is conveyed through Charlie's (Harvey Keitel) attempt to remain loyal to his uncle Giovanni against the ninjo, envisioned in his profound Catholic background, which forces him to help Johnny Boy (Robert de Niro), and his love for his cousin Teresa. The plot develops as follows:

"Charlie"

"Charlie"

(Harvey Keitel)

|

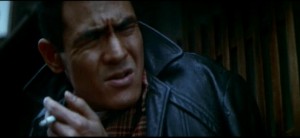

Oscar, owner of a restaurant, cannot make a payment to Giovanni, Charlie's uncle. This restaurant will become Charlie's, but Giovanni disapproves of his involvement with Johnny Boy (Robert de Niro) and thinks of Teresa, Johnny Boy's cousin and Charlie's secret girlfriend, as being crazy, she is in fact epileptic. If Charlie wants the restaurant, and secure his future, he has to stop intervening in the dispute between Johnny Boy and Michael (Johnny Boy owes money to Michael). His religious convictions are confronted with the economic matters of real life. To make things worse for Charlie, Teresa asks him to move to a flat and live together.

In his book Hollywood Genres, Thomas Schatz perfectly describes Charlie's internal conflict when he analyses the downfall of the gangster hero: "This internal conflict- between individual accomplishment and the common good, between man's self-serving and communal instincts, between his savagery and his rational morality- is mirrored in society, but the opposing impulses have reached a delicate and viable balance within the modern city. The gangster's efforts to realign that balance to suit his own particular needs are therefore destined to failure" (12). David Desser, discussing the giri-ninjo conflict in the post-war samurai film, explains how "in Japanese life the giri/ninjo conflict is unresolvable" and consequently "when confronted by the giri/ninjo conflict, the hero of the Nostalgic Samurai Drama makes his choice knowing full well the price to be paid in social alienation and/or self-abnegation" (13). In Charlie's case there are several conflicting things that threaten to destroy him. First of all, it is his loyalty to uncle Giovanni, seen as the authority figure of the neighborhood (the oyabun figure in the yakuza film), somebody who oversees order in the community. Secondly, it is Charlie's sense of penance which is materialized in the shape of Johnny Boy.

|

This is precisely what a voice-over, perhaps the voice of God, tells Charlie when Johnny Boy makes his first appearance at Tony's bar, Charlie's friend. Another important reason why Charlie has to help Johnny Boy is family ties. The family, either by blood or by association, remains the soft spot of the hero in the gangster film, which ensures the protagonist's destruction (14). Charlie's strict religious convictions reprove all he does, collecting payments for his uncle Giovanni, and feels, his fixation with the female black dancer at Tony's bar, which sets him against the racism of his Italian American buddies. All these factors create a state of permanent guilt and a strong desire to be punished. In the context of the gangster genre, Charlie's internal struggle to achieve a moral balance is, therefore, doomed. As Schatz points out, the main flaw in the gangster hero is " his inability to channel his considerable energies in a viable direction" (15). As the voice-over tells Charlie right at the beginning of MEAN STREETS: "you don't make out for your sins in the church, you do it in the streets, you do it at home...". Charlie spends all his energy to do just that, to keep his uncle happy and to save Johnny Boy, but eventually fails to maintain the delicate balance between giri and ninjo.

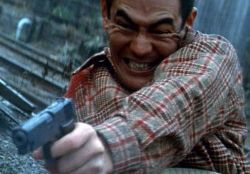

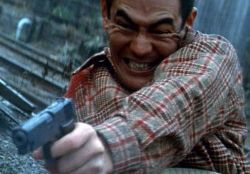

"Shozo Hirono"

"Shozo Hirono"

(Bunta Sugawara)

|

In contrast, Kinji Fukasaku seems to take up the themes and purposes of the earlier Hollywood gangster films of the 1930s. As McDonald explains he "puts its subject in a broad social context: modern Japan in the twenty-five year period ending in 1970" (16). Fukasaku's films question the values of post-war Japan by linking the ascension of the Yamamori gang in JINGI NAKI TATAKAI with that of Japan itself. This mirrors the rise to power, for example, of the gangster Tom Powers (James Cagney) in THE PUBLIC ENEMY. JINGI NAKI TATAKAI's protagonist, Shozo Hirono (Bunta Sugawara), is a member of the Yamamori gang unable to adjust to the socio-economic transformation taken place in his clan as he still blindly follows the jingi code. The yakuza conversion into businessmen and Hirono's out of step with the times recall the situation faced by Walker (Lee Marvin) in John Boorman's POINT BLANK(1967) or Frankie Madison (Burt Lancaster) in Byron Haskin's I WALK ALONE (1948). |

When Hirono gets involved in a fight with a member of a rival gang he decides to follow the ritual of cutting his little finger (yubitsume) and presents it wrapped in a white cloth to the rival gang's oyabun to appease the wrath of his own boss Yamamori. Yamamori, in fact, makes fun of Hirono by saying that the cutting of a finger will not cost Hirono anything and that he would better pull a job to get money for the clan. Hirono, even though faithful to the jingi code, has no idea of have to perform yubitsume. Fukasaku gives the sequence a comical tone to scorn the yakuza ceremonial that permeates the ninkyo eiga. The fact that the significance of this important ritual is not taking seriously is highlighted when, as Hirono is offering his finger to the rival oyabun, this one says that there was no need to go to such extremes for such a silly fight. Later, Hirono will kill another rival oyabun to save his own boss and then agrees to go to jail when Yamamori offers him the running of the gang after he is released. Once again, Hirono, sticking to the code of jingi, is used and betrayed by his own boss. Similarly, Charlie abides faithfully by his religious beliefs to atone for his sins when, unconvinced of the effectiveness of the usual penance of Our Fathers and Hail Marys given in confession, he appears to immolate his right index finger in the flame of a votive candle before a church altar. Right before he holds his finger over the flame he says, "I do something wrong, I just wanna pay for it my way. So I do my own penance for my own sins." Therefore, Hirono and Charlie are portrayed as anachronistic figures, adherents to extreme acts of atonement which are mocked by their peers and even bosses.

So it could be argued that Scorsese's MEAN STREETS has much in common with the classical yakuza films or ninkyo eiga and that Fukasaku takes on the social and historical issues that are normally seen in the classical gangster film. MEAN STREETS, an independent production, is much closer in content rather than style to the conventions of the gangster film genre of the Old Hollywood. Conversely, JINGI NAKI TATAKAI, a studio production, emerges as a more challenging film to genre conventions. Furthermore, as Fukasaku himself has commented his "contribution to the development of Japanese cinema was to abolish the star system" (17). In short, to abolish the star vehicle film in which audiences expectations were duly met according to the actor's star persona. Fukasaku's remarks place him closer to the environment in which MEAN STREETS was born, the New Hollywood cinema, where the director took a more prominent role in detriment of the actors. Despite this, Fukasaku was, for the most part of his career, a studio director working on studio assignments, producing a myriad of films many of them quite conventional.

During the so-called New Hollywood period of the end of the 60s and beginning of the 70s, directors gained more control over their work. Certainly, the work of the French nouvelle vague had an enormous influence on New Hollywood film directors, particularly the technical innovations that the former brought into filmmaking. Lightweight camera equipment and more sensitive film stock could be used in location shots with only available light, given the films an air of cinéma vérité. Film techniques employed such as jagged editing or jump-cutting were both theoretically and materially motivated. It is difficult to evaluate to what extent Fukasaku was influenced by nouvelle vague's works. Admittedly, he regarded French crime films such as Clouzot's QUAI DES ORFEVRES (1947) or Jacques Becker's TOUCHEZ PAS AU GRISBI (1953) more highly than the GODFATHER films (18). Japan had its own New Wave with Nagisa Oshima leading its way. Oshima, rather that acknowledging any influence from his French counterparts, cites the works of Yasuzo Masumura and Ko Nakahira as having an enormous impact on his own work. (19 ).

As mentioned earlier, MEAN STREETS and JINGI NAKI TATAKAI were made under the influence of, or in response to, very different film cultural contexts, The Classical Hollywood and European Art Cinema and the ninkyo eiga respectively. Adding to this was the influence that the style and content of documentaries produced in their own countries had on both filmmakers. Scorsese recalls that he "witnessed American daily life etched for the first time on American screens in unsanitized, ethnically diverse images by the New American Cinema documentarists" (20). Fukasaku's use of the hand-held camera started after viewing newsreels from the student movements where images showed university students and farmers fighting the police (21), perhaps referring to the documentary films that Shinsuke Ogawa made between 1968 and 1973 focusing on the protests of rural villagers and farmers around the village of Sanrizuka against the construction of Narita International Airport (SUMMER IN NARITA, THE THREE-DAY WAR IN NARITA, PEASANTS OF THE SECOND FORTRESS, THE BUILDING OF THE IWAYAMA TOWER and HETA VILLAGE).

Fukasaku believes he first began to use a hand-held camera in HITOKIRI YOTA (1972).In fact, it was in an earlier film made that year, GUNKI HATAMEKU MOTO NI, in which he employs this film technique as well as peppering the screen with photographic stills taken at the New Guinea front during World War II. The film follows the widow (Sachiko Hidari) of sergeant Togashi (Tetsuro Tanba) in her search to discover what really happened to her husband, executed for desertion in New Guinea. Whereas the main story is shot in colour, the reminescences of her husband's comrades whom she interviews are conjured up in flashbacks shot in black and white to intensify the documentary feeling. So despite different cinematic backgrounds, Scorsese's and Fukasaku's similarities are found in their depiction of violence and demystification of the gangster while resorting to documentary film techniques to infuse their work with a greater sense of realism and immediacy to the people portrayed in their films.

The correspondence between both films is best revealed in their first minutes. MEAN STREETS opens as Charlie is awakened by a voice-over that is quite disorientating, specially since it is not Charlie's own voice (but, in fact, Martin Scorsese's). The voice-over emphasises what the mise-en-scene reveals, an austere room and a spotlighted crucifix on the wall, Charlie's struggle between his religious convictions and his rough environment and unlawful activities and friends within the city as backdrop. The handheld camerawork follows the tormented Charlie around the room. Jump-cuts, punctuated by the first notes of "Be My Baby" by The Ronette's, are used after Charlie returns to the bed and falls asleep again. This sequence is followed by the main title credits, accompanied all along by the same song on the soundtrack, which consist of a home movie footage of the christening of a little boy from Charlie's family and the subsequent party where the main characters of the film are introduced.

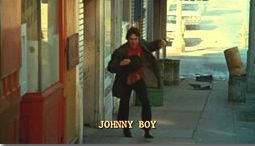

"Johnny Boy"

"Johnny Boy"

(Robert de Niro)

|

The use of jerky home movie footage in this scene has the effect of bringing us closer to the characters participating in the rituals of life, a stark contrast to the elaborated opening scene in the THE GODFATHER. Once the title credits end, there is a long shot of a religious procession in Little Italy. The shaky and black and white 8 mm home movie footage is transformed into the normal world of the movie itself shot in colour 35 mm film of the movie that perfectly situates the story in a specific spatial context. From this point, the four main characters are presented in a rather long introduction, which provides the first traits of each character's personality. Charlie is the religiously repressed and guilty one; Tony runs a bar and also has a strong sense of morality; Michael is the racketeer, easily fooled; and Johnny Boy is the crazy one. The establishment of each character ends with a freeze-frame and the superimposition of their names on the screen. |

The opening sequences of JINGI NAKI TATAKAI are starkingly similar. A still photograph of the mushroom cloud covering the sky of Hiroshima, accompanied by Toshiaki Tsushima's dramatic soundtrack, irrupts into the film. The photograph is followed by several others of the city right after the bombing and newspaper captions. Then the narrative shifts to moving images, still in black and white, of a Hiroshima public market, which metamorphoses into the colour and anamorphic images of the film proper. The attempted rape of a Japanese girl by American G.I. and the scuffles that follow are shot by Fukasaku with a shaky hand-held camera. The images come to an abrupt stop every time the main characters are introduced, one by one, in freeze-frames with their names superimposed on the screen.

|

The beginnings of both films are far from being identical but both employed a significant number of similar stylistic devices to achieve identical purposes. The home-movie footage of MEAN STREETS and the black and white stills and initial scene, also filmed in black and white, of the Hiroshima market, with which JINGI NAKI TATAKAI open, grants these works an appearence of filmed document as they place the narrative in a very specific historical, cultural and spatial context. The freeze-frame and titles superimposition underline the influence that documentary or cinéma vérité had on both directors. Shared film techniques and the films' plotlines work to demystify the yakuza and gangster film genres. Mark Schilling notes that "in the late 60s, directors such as Kinji Fukasaku, Kosaku Yamashita and Junya Sato began making yakuza movies that more nearly reflected contemporary realities, with a gritty violence and brutality that had little to do with the ideals of giri and ninjo, everything to do with life and death on Japan's mean streets" (22).

Another feature that links these both films is their autobiographical source. This is more prominent in Scorsese's film, since some of its characters are based on friends of the director and some of the events actually happened to him. As Scorsese himself has explained "Mean Streets was an attempt to put myself and my old friends on the screen, to show how we lived, what life was in Little Italy. It was really an anthropological or a sociological tract"(23). The autobiographical elements are less obvious in Fukasaku's film, but JINKI NAKI TATAKAI are based on real events. The story is adapted from a novel by the journalist Koichi Iiboshi that was created using his interviews to the imprisoned former boss of the Mino gang, Kozo Mino (24). Just before his death, Fukasaku remarked that in making a new sort of youthful and violent film, as what he has done in his last complete film BATTLE ROYALE, he "wanted to replace the old techniques with a new kind of film, where I could overlay my own experiences of living in post-war Japan" (25). The end of that war brought for the young Fukasaku the total collapse of all the values he had learnt at school: authority, nation, honour, etc. (26). Fukasaku saw the end of the war as the beginning of a state of anarchy where friendship and camaraderie are put to the test, a view that becomes the main motif in BATTLE ROYALE. This theme also constitutes one of the main elements in MEAN STREETS as Charlie tries to help his closest friend Johnny Boy against a menacing environment that threaten to destroy their friendship. |

The connections between MEAN STREETS and JINGI NAKI TATAKAI go beyond their achievements in terms of subversion of genre conventions or unorthodox visual elements. These films have influenced enormously the yakuza and gangster films that followed. So it should not come as a surprise that in 2009, conmemorating its 90th anniversary, Kinema Junpo, Japan's oldest and most eminent film magazine, selected JINGI NAKI TATAKAI as the fifth best film in the history of Japanese cinema (27). Meanwhile, MEAN STREETS is often described, along with THE GODFATHER, as one of "the two most important gangster films of the seventies" (28). The narrative and stylistic innovations of Fukasaku's film were soon embraced by its own production company, Toei, in making more jitsuroku eiga. To add more realism to these new yakuza films, former gangsters such as Noburo Ando were cast in significant roles. Ando had a small part in JINGI NAKI TATAKAI and starred in several films such as BORYOKU GAI (The Violent Street, 1974) and ANDO NOBORU NO WAGA TOBO TO SEX NO KIROKU (Noboru Ando's Chronicle of Fugitive Days and Sex, 1976). Later he directed his own films such as YAKUZA ZANKOKU HIROKU - KATAUDE SETSUDAN (Yakuza Cruel Secrets- Arm Dismemberment, 1976). The decline in popularity of yakuza films started to be felt in the box office in the mid-1970s.

In the 1990s, however, independent directors such as Takashi Ishii, Takeshi Kitano, and more recently Takashi Miike, have tried to redefine the genre. The graphic violence depicted in their films recalls Fukasaku's own view of the savage world of the yakuza. Aaron Gerow sees Kinji Fukasaku as the inspiration for Miike's "apocalyptic nihilism and sympathy for Japan's social marginals" (29). These characteristics are also shared by Ishii's film GONIN (1995), where the five main characters of the story represent five types of outcast in the structure of Japanese society: A former pop-singer, who is secretly gay; a disgraced policeman who has just being released from prison; a recently fired salariman; a simple-minded ex-boxer turn pimp with a crush on a Filipino illegal immigrant, and a gay blackmailer.

GONIN has often been compared to Quentin Tarantino's PULP FICTION (1994), a director that, just like his Japanese counterparts, had tried to redefine the gangster film in his films from the 90s. Narrative and visual virtuosity and, particularly, the extensive use of a soundtrack of popular songs are elements of Tarantino's work taken from the example of MEAN STREETS. Scorsese arranged whole scenes in MEAN STREETS to the tune of an ecletic selection of mainly rock, soul and pop songs he grew up with. Regarding MEAN STREETS, Scorsese has said "the whole movie was 'Jumping Jack Flash' and 'Be my baby'" (30). Another connecting element from MEAN STREETS can be found in Guy Ritchie's works. One of the most obvious lifts from MEAN STREETS in Richie's first feature film LOCK, STOCK AND TWO SMOKING BARRELS is the use of the snorry-cam (a camera that it is fixed to the actor's body)after one of the protagonists, Eddy (Nick Moran), loses 100,000 pounds on a bad poker hand. In MEAN STREETS the same technique was used to follow a drunken Charlie as he staggered around Tony's bar. In his second film SNATCH, Ritchie's complicated narrative uses several interlocking stories, flashy camerawork, and an almost unbroken soundtrack of popular tunes.

JINGI NAKI TATAKAI and MEAN STREETS similarities extend beyond simply film techniques or narrative innovations. Their release in 1973 marks a break in the way that yakuza and gangster films were conceived afterwards. Their influence on a new generation of filmmakers trying to revive the gangster film genre since the 90s is a clear reflection of their importance in the history of the yakuza and gangster film.

Notes

- Schilling, Mark Yakuza Films: Fading Celluloid

Heroes (Japan Quarterly, July-September 1996, vol. 43, 6), p. 30.

- Schrader, Paul Yakuza-Eiga: A Primer (Film

Comment, 1974 vol. 10, 1), p. 10.

- Japanese Wikipedia, Mean Streets.

- Nolleti, Arthur and Desser David Reframing

Japanese Cinema: Authorship, Genre, History (Indiana University Press, 1992), p. 174.

- Ibid, p167.

- Ibid, p190.

- Barrett, Gregory Archetypes in Japanese Film

(London: Associated University Presses, 1989), p.64.

- Schrader, Paul, p.10.

- Ibid, p12.

- Fukasaku, Kinji and Yamane, Sadao, Eiga Kantoku Fukasaku Kinji, Tokyo, Waizu Shuppan, 2003, pp 270-71.

- Macias, Patrick TokyoScope:The Japanese Cult

Film Companion (San Francisco: Cadence Books, 2001), p. 154.

- Schatz, Thomas Hollywood Genres (Boston:

MacGraw-Hill, 1981), p.85.

- Nolleti, Arthur, p.150

- Ibid, p.94.

- Ibid, p.94.

- Nolleti, Arthur, p. 184.

- Macias, Patrick, p. 185.

- Desjardins, Chris, Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film, I. B. Tauris, 2005, p. 24.

- Desser, David Eros plus Massacre: An

Introduction to the Japanese New Wave Cinema, (Indiana University Press,1988), p. 41-43.

- Thompson, David and Christie, Ian Scorsese on

Scorsese, (London: Faber and Faber, 1989),p. xx.

- Macias, Patrick, p. 154.

- Schilling, Mark, p.40

- Thompson, David and Christie, p.48.

- Macias, Patrick, p. 141.

- Ibid, p.153.

- Gerow, Aaron, Fukasaku Kinji: Underworld

Historiographer.

- Oru Taimu Besuto Eiga Isan 200. Nihon Eiga Hen, Tokyo, Kinema Junposha, 2009, pp. 1-20.

- Hardy Phil, Gangsters (London: Aurum Press,

1998).

- Gerow, Aaron.

- Thompson, David and Christie, Ian, p. 45

Bibliography

Barrett, Gregory (1989) Archetypes in Japanese Film, Associated University Presses, London.

Bordwell, David and Thompson, Kristin (1994) Film History: An Introduction, McGraw-Hill, London.

Cook, David A. (1996) A History of Narrative Film, WW Norton & Company, London.

Desser, David Towards Structural Analysis of the Postwar Samurai Film in Nolleti, Arthur and Desser David, Reframing Japanese

Cinema: Authorship, Genre, History (1992) Indiana University Press.

Desser, David (1988) Eros plus Massacre: An Introduction to the Japanese New Wave Cinema, Indiana University Press.

Desjardins, Chris (2005) Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film, I. B. Tauris.

Gerow, Aaron,

Fukasaku Kinji: Underworld Historiographer

Hardy, Phil (1998) Gangsters, Aurum Press, London.

Fukasaku, Kinji and Yamane, Sadao, Eiga Kantoku Fukasaku Kinji (2003), Waizu Shuppan, Tokyo.

MacDonald, Keiko "The Yakuza Film: An Introduction" in Nolleti, Arthur and Desser David, Reframing Japanese Cinema: Authorship, Genre, History (1992) Indiana University Press.

MacDonald, Keiko "Kinji Fukasaku: An Introduction". Film Criticism, (1983), vol.8 (1): 20-32.

Macias, Patrick (2001) TokyoScope:The Japanese Cult Film Companion, Cadence Books, San Francisco.

Martin, Richard (1997) Mean Streets and Raging Bulls: The Legacy of Film Noir in Contemporary American Cinema, The Scarecrow Press, London.

Mellen, Joan (1975) The Waves at Genji's Door: Japan Through its Cinema, Pantheon Books, New York.

Oru Taimu Besuto Eiga Isan 200. Nihon Eiga Hen (2009), Kinema Junposha, Tokyo.

Schatz, Thomas (1981) Hollywood Genres MacGraw-Hill, Boston.

Schilling, Mark (1999) Contemporary Japanese Film, Weatherhill, New York.

Schilling, Mark. "Yakuza Films: Fading Celluloid Heroes". Japan Quarterly (July-September 1996), vol. 43(6): 30-42.

Schrader, Paul "Yakuza-Eiga: A Primer" Film Comment (1974) vol. 10(1):8-17.

Standish, Isolde (2000) Myth and Masculinity in the Japanese Cinema: Towards a Political Reading of the "Tragic Hero", Curzon, London.

Thompson, David and Christie, Ian, eds. (1989) Scorsese on Scorsese, Faber and Faber, London.

©EigaNove (Joaquín da Silva)Date of Publication: 07/11/2003

Revised and updated: 5/9/2015

JINSEI GEKIJO: HISHASAKU

JINSEI GEKIJO: HISHASAKU

THE PUBLIC ENEMY

THE PUBLIC ENEMY

"Charlie"

"Charlie"

"Johnny Boy"

"Johnny Boy"