January

In a New Year's article, the Osaka Asahi Newspaper wrote about the theatrical business success of the twin brothers Otani Takejiro and Shirai Matsujiro. It was titled "Matsutake no Shin Nen" (Matsutake's New Year), Matsutake being a combination of their first characters of their surnames. The article popularised the company's new denomination which led to the foundation of Matsutake Gomei-sha (Matsu Take Partnership Corporation). Though the company's roots were in the Kyoto and Osaka area, its activities dating back to December 1895, by 1910, Matsutake had made headway west acquiring theatres in the Tokyo area. By 1923, the brothers controlled nearly all the theatres used by kabuki and shinpa (Leiter, p.30).

When their business was expanded in 1920 to include motion-picture productions, the company was renamed Shochiku Kinema Gomei-sha, Shochiku being an alternative reading of Matsutake. As Jasper Sharp states the new film production company "immediately set forth its ambition of breaking away from the jidai-geki period swashbucklers that dominated the early market and of producing films that utilized the acting and stylistic techniques being pioneered in Western cinema" (Sharp, p.222). That same year a film studio was built in the town of Kamata, between Tokyo and Yokohama, where the company's first film was produced, SHIMA NO ONNA (Island Woman), directed by Kotani Henri, a Japanese-born who emigrated to the United States with his parents when he was a boy and worked as a cinematographer and actor at the Jesse L. Lasky Company in Hollywood. SHIMA NO ONNA was starred by Kawada Yoshiko and Nakamura Tsuruzo and released on 1 November 1920. Shochiku Kinema Gomei-sha adopted its present name, Shochiku Kabushiki-gaisha (Shochiku Co., Ltd.), in 1937.

Sources:

Shochiku, History of Shochiku.

Jasper Sharp, Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema, Scarecrow press, 2011, pp. 222-23.

Samuel L. Leiter, Kabuki at the Crossroads: Years of Crisis, 1952-1965, Global Oriental, 2013, p. 30.

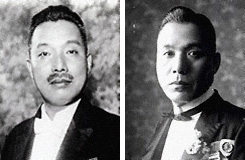

Shirai Matsujiro (L) and

Otani Takejiro (R)